Bridging the Gap Between Architecture and Landscape Architecture

Written by: Sophia Triantafyllopoulos

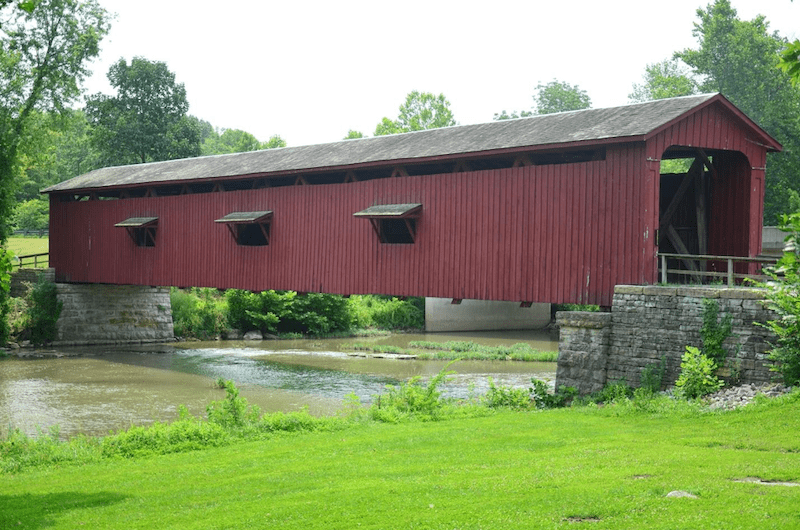

My fascination with the built and natural environment stems from my upbringing in Indiana and was what ultimately led me to pursue two degrees in architecture. Car rides across town or visits to parks were always followed by a familiar landscape consisting of rustic barns, glistening grain silos, homesteads, and covered bridges. Between the meadows and fields, main streets set the scene for city gatherings and old warehouse and manufacturing districts became a place of teenage exploration. They offered a glimpse into the past, connections to history classes, and were followed by countless opportunities to wonder about the rich stories these places held. As I grew older, I began to realize that the buildings, sites, and landscapes ubiquitous to Indiana and the Midwest would not exist without their surrounding context.

Upon first glance, the only similarities between landscape architecture and the field of architecture are that they both share a common end name and fall under the design umbrella. Throughout my undergraduate and early graduate architecture courses, the relationship of a site to our studio design projects was highly stressed – initially that is. However, after a few weeks of precedent studies and design iterations, site context quietly fell into the backdrop as the building design took center stage. Any discussion regarding existing site conditions or treatment became lost in a banter of façade details, program arrangement, circulation, and so on. The absence of thorough historical site analysis where I could dive into the various environmental, social, political, and economic conditions that established connections between people and their natural and built environments led me to pursue a PhD in architecture with a historic preservation certificate.

With a focus on historic preservation careers, I was confident I would primarily concentrate on buildings, in the singular sense. It had never occurred to me that landscape architecture would be a key part of historic preservation. It was not until I began my internship at the National Park Service (NPS), Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (OCLP) that I began to see the commonality of interests between the two professions and how essential they are for preserving the unique historic and cultural landscapes across the United States. While both are unique in scope of work (i.e. an architect works on rehabilitation efforts for a building, and a landscape architect seeks to preserve plantings and other natural or built site components), their tasks are not independent from one another, rather they both contribute to wholistically preserve an environment or site. Combined, their efforts contribute to the continuation of these special places so that the public is able to appreciate, use for enjoyment, and on-going education efforts that the NPS strives to achieve.

My internship role as the OCLP digital media specialist follows the NPS mission of educating the public. In a way, NPS is doing this through the creation of cultural landscape profiles to establish understanding and interest for our nation’s diverse cultural landscapes. To achieve this, it is vital that profiles and other material produced are created in an approachable manner. This requires removing professional jargon and synthesizing details from lengthy cultural landscape reports, inventories, and other carefully curated documents to create a profile that captures a site’s essence. In addition to relaying stories, the profiles also aid in emphasizing established relationships between landscape, built environment, and the community in which these sites served. History has shown that over time, built or cultural landscapes do not evolve in a vacuum. Context is very important in understanding the complete picture.

Although I have recently begun my internship, I am constantly reminded about the intimate moments I have had with the surroundings I called home, whether in suburban Indiana, bluegrass Kentucky, small town Kansas, a hilltop town in Italy, or my current home in downtown Cincinnati. Context helps build a better perspective which in turn helps me take in more of my surroundings.