Where Do Artifacts Go?

by: Mariah Walzer

These past two weeks have been a jumble of different duties and experiences, so trying to find a theme for this week’s blog post felt a little daunting. But then I realized that much of the work centered on what happens to artifacts and other objects after they are discovered.

For example, I spent a day doing my best to identify the artifacts we found during our surveys the last few weeks. As I mentioned in my previous post, identifying the types of projectile points can be very useful, because the types can suggest or confirm dates for the site. I managed to identify fairly confidently two of the projectile points (a Madison point and a Bare Island point) but the quartzite point could be any of four different types. We also found some pieces of bone that I think are turtle shell fragments, though I’m not 100% sure.

Bone fragments found during survey. The jagged edges (known as sutures, where bones will eventually fuse together) and the shallow lines across the top of the bones suggest that these may be pieces of a turtle shell.

In archaeology, you learn to be okay with unknowns and maybes. We can’t go back in time and ask the peoples we study, so often we are just throwing out our best guesses based on the things we do know, observed behaviors of other people (called ethnography), and our own common sense. It’s kind of like trying to draw the missing piece in a puzzle – you know roughly what it should be based on the pieces around it, but you can never know exactly what it looked like. Because of this, critical thinking and a healthy amount of skepticism are essential for an archaeologist!

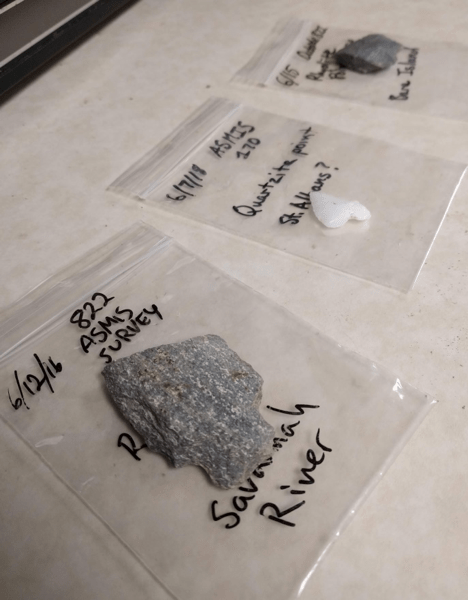

My notes from trying to identify this quartzite point. Its common shape and broken tip and left shoulder contribute to the difficulty in identifying this point.

This past week, I spent time at the Museum Resource Center for the Capital Region of the NPS. I learned how to clean artifacts to prepare them for study and storage. Each artifact material type – faunal, lithic, ceramic, fabric, metal, and more – has to be cleaned and cared for in the best way to preserve it. For tough materials like lithics and glass, they can be washed with water and a toothbrush. But bone and metal should not be exposed to water, so they must be dry-brushed.

After artifacts are cleaned, they are put in bags that are labelled with locational information. The bags also have holes poked in them so that changes in humidity will not hurt the artifacts.

Then I learned how to catalogue artifacts, so that we know what have, where the artifacts came from, and where we can find them in the storage facility. This is a tedious process, but it is very useful for future researchers. There are millions of artifacts stored in the Museum Research Center so knowing where to find the horseshoes from Monocacy, for example, is essential.

In addition to these artifact-centered experiences, I also helped clean a monument, attended an orientation for NPS Cultural Resources interns in Washington DC, and dug my first shovel test pits (small holes dug to determine the soil layers of an area and to check for the presence of significant archaeological sites). Every day really is a new experience here!