Welcome HOME

By: Sabrina Gonzalez-Morabito

Sabrina Gonzalez-Morabito at HOME

This summer, I am excited to be an ACE CRDIP Historian Intern at Homestead National Monument (HOME). What makes this summer special is the 19th Amendment centennial that HOME is celebrating with hundreds of other parks across the country including the Women’s Rights National Historical Park and Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument. One connection that Homestead NM has with the suffrage movement of the 19th and 20th century is the Homestead Act of 1862. It was signed into law by Abraham Lincoln and enacted on January 1st, 1863. This act allowed for men, women that were head of the household, former slaves, and immigrants to stake their claim of 160 acres. The requirements were roughly fifteen dollars, 21 years of age, and to live on the land for five years with some sort of cultivation and establishment completed. Another significant connection is that out of the thirty homesteading states, twenty-four of them allowed women’s suffrage before the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. This answer is rooted in the looser social and political structures that Western states obtained as they were forming their states’ constitutions. For Eastern states, the fight to ratification involved rewinding the gender norms and traditions that embodied them.

My part in this work is accompanied by Jonathan Fairchild, the Historian at HOME. Together we are working on continuing the story titled “Planted in the Soil”. This talks about the vast connections that the Homestead Act of 1862 has with the Suffrage Movement. It is important to note that women-based organizations began to become increasingly mobilized in the 19th century. The advancements from transportation to education, challenged socioeconomic norms to allow women to have greater accessibility in support of public awareness and assembly. More women began to become part of voluntary associations that aimed toward political reform. This makes it no surprise that there were an abundant amount of independent women involved in homesteading that were fighting for women’s equality during this time.

Felice Cohn’s story, a Jewish woman from Nevada, provided the poster-child example. She was the founding member of the Nevada Equal Franchise Society in 1911, President of the Nevada Voter’s Club in 1917, and drafted the legislative resolution that led to the women’s suffrage in Nevada. In 1916, she travelled to the District of Columbia to work on land related issues with the Department of Interior. While Felice was there, she was honored by the Commissioner of the General Land Office. Two years later she was appointed the hearings attorney for the United States Land Office.

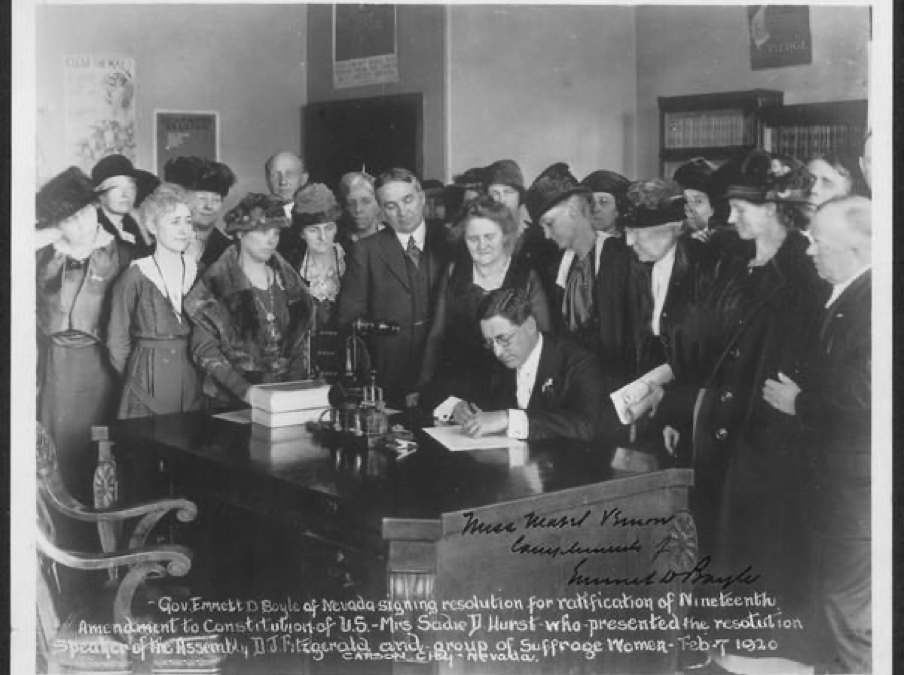

Governor of Nevada, Emmett D. Boyle, signing the 19th Amendment Feb. 7, 1920

In order to own any land from the Homestead Act, an individual would have to make a claim at the local General Land Office. Felice Cohn’s story provides the logistics perspective to homesteading as a lawyer for the GLO. I am researching more of her work to add to the story that we are telling at Homestead National Monument of America.

Another woman that I am researching is Rachel Bella Kahn (Calof). Her story provides the perspective of the immigrant homesteader’s wife. Her history is based on the manuscript that she wrote in 1936. She set out to publish her work in The Forward, a Yiddish newspaper based in St. Paul, Minnesota, but was inauspicious. It was not until 1995 that her story was translated by Jacob Calof and Molly Shaw. It was published by the Indiana Press University, and titled Rachel Calof’s Story: Jewish Homesteader on the Northern Plains. On behalf of their efforts her story lives on.

Rachel Calof, 1949

In 1876, she was born in present day Ukraine. Her triumphant story begins here with her mother’s passing at a young age; she “assumed the role of protector of [her] brothers and sisters” before she reached early adolescence. At the age of eighteen, her forthcoming career consisted of no path. It was not until Rachel Chavetz, the shochet’s daughter, denied the marriage arrangement to Abraham Calof, a Jewish immigrant living in the United States. Rachel Kahn was the subsequent choice to marry the eligible bachelor. Shortly after the accepted marital, Abraham organized her travel from the Ukraine to Ellis Island, where the two birds met for the first time. The pair were on their way to the pioneer after two weeks. Abraham’s family moved to North Dakota three months prior to Rachel’s arrival and homesteaded near Devil’s Lake in Ramsey County.

Her story in North Dakota is filled with courage and strength. After living on the homestead for over a decade, the Calof family decided to move to St. Paul, Minnesota. While there, Rachel joined multiple religious organizations. Two of them were the Jewish Pioneer Women’s Club and the Auxiliary Workmen’s Circle. Did these organizations fight for women’s equality? That is the question that I am currently researching.